Impact Sensors: A Missing Piece of Head Injury Programs

IF YOU WATCHED the Super Bowl LII earlier this month, you’ll recall a moment in the second quarter when Patriots quarterback Tom Brady found Brandin Cooks wide open for a beautiful, 23-yard completion. But when Cooks turned to run for the end zone, he didn’t see Eagles safety Malcolm Jenkins gunning for him on the left. Like Jaws, Jenkins roared out of the murky deep, and leveled Cooks with a vicious hit to the head.

In close-ups, you can see Cooks’ head bobble on his shoulders before he crumples to the ground. He briefly loses consciousness, and after he’s walked off the field, he doesn’t return for the rest of the game. That’s because of the NFL’s concussion safety protocol—a process that mostly involves checking for vague symptoms like “a blank look”, and which is currently undergoing extensive revision for its failure to protect players from serious injury.

It’s no secret that the NFL has a concussion problem. Countless players have demonstrated the long-term effects of repetitive head injury, which are so gruesome that the likes of Barack Obama and Justin Timberlake have said they would never let their kids play football.

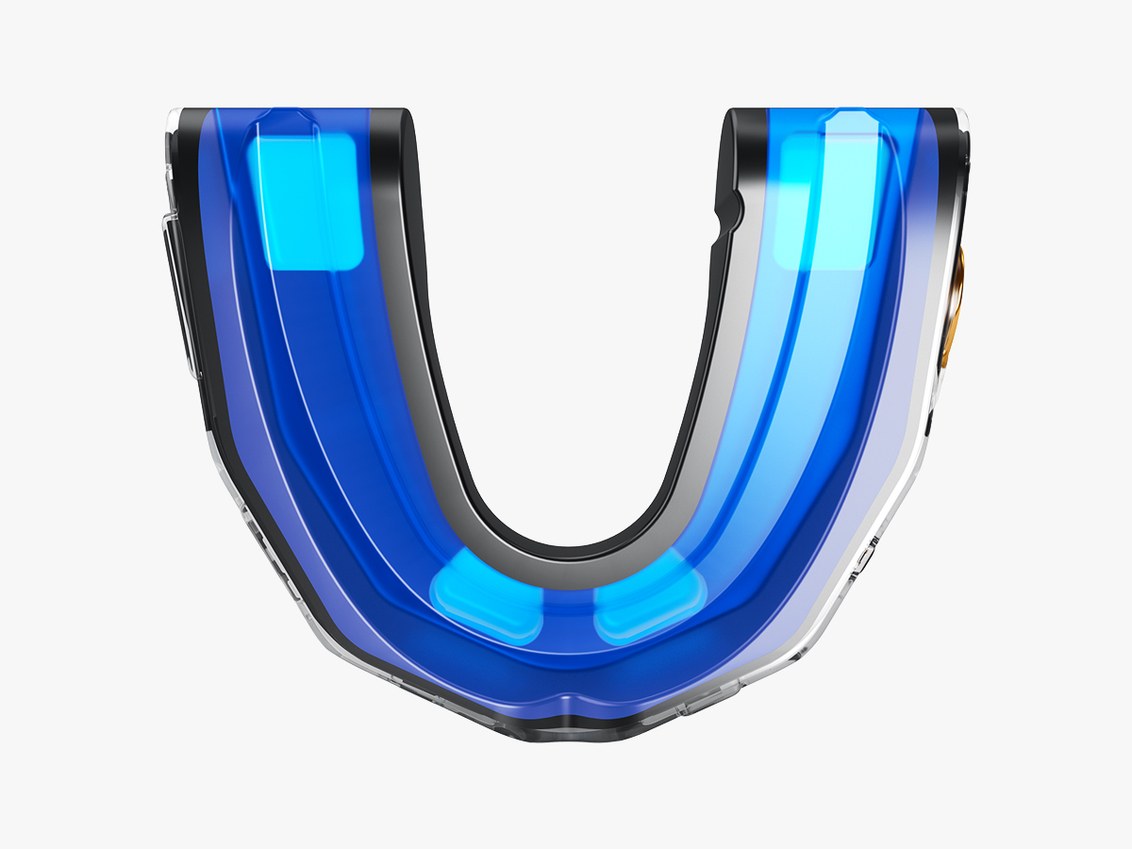

In 2016, the League pledged $60 million toward developing better player safety equipment for players. One company, Prevent Biometrics, believes they can help the NFL achieve that goal by providing better data. With their new mouthguard-mounted head impact monitoring system, Prevent Biometrics hopes to help researchers collect as much data about head impacts as possible. And with that data, they hope to change how athletes and coaches deal with concussions for the better.

Cool Runnings

The quest to accurately monitor head impacts dates back to the 1950s, beginning with the research of Dr. John Paul Stapp. An Air Force flight surgeon, Stapp used himself as a test subject to study the effects on acceleration and deceleration on the human body. He’s been called a “human crash dummy” for his contribution to understanding how the skull responds to impact—and how to make planes and cars safer in the event of a crash.

In sports, those impacts have normally been measured with helmet-mounted sensors. The Riddell Sideline Response System (SRS), a helmet-mounted head impact monitoring system, have been available for sale since 2004. But data collected from those sensors is flawed, because helmets move differently than human heads do. That’s part of the reason the NFL announced in 2015 that it was indefinitely postponing the use of concussion-monitoring systems until a more accurate method could be found.

Now, it looks like there is one: a mouthguard. Athletes who play sports sans-helmet, like boxers or wrestlers, often wear mouthguards. And more importantly, the data those mouthguards collect is far more accurate than a helmet sensor, since the mouthguard is directly coupled to the skull through the teeth.

Dr. Adam Bartsch had been thinking about a sensor-mounted mouthguard for over a decade before he became the chief science officer at Prevent Biometrics. I first met Bartsch at the 2018 Consumer Electronics Show, where he was casually swinging a sledgehammer into a child-sized crash test dummy’s head.

Bartsch was just a graduate student in mechanical engineering at Ohio State when he first heard of the idea of monitoring head impact through a mouthguard.

“In 2003 I attended a talk given by Dr. Stefan Duma from Virginia Tech on the first sensor data obtained from a helmet-mounted system in football,” Bartsch says. “Dr. John Melvin, who was the preeminent safety engineer in the audience, asked a question about mounting the sensors in a mouthpiece to get better coupling. I remember thinking, ‘That sounds like a great idea.’”

It wasn’t until around 2008 that Bartsch—by then, the director of the Head, Neck, and Spine Research Laboratory at the Cleveland Clinic—began talks with Dr. Vincent Miele about the idea. A professor of neurological surgery at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Miele is also a boxing aficionado and longtime ringside physician. He realized that boxers were suffering unnecessarily because a referee, like a coach, calls knockouts based entirely on subjective evidence. Like Bartsch, he theorized that there must be a way to accurately measure head impacts and turn the call into an objective, data-driven process.

Bartsch and Miele put the idea to Dr. Edward Benzel, the chairman emeritus of the Cleveland Clinic’s department of neurosurgery, and Lars Gilbertson, the director at the Cleveland Spine Clinic. The goal was to develop a monitoring system for professional and amateur boxers. The team collected grants from organizations like the National Institutes of Health and the Department of Transportation to develop the technology. When they tested it in laboratory settings and with young boxers and football players, Prevent’s mouthguard was able to accurately measure head impacts to within 5 percent of the impact’s true value, unlike other monitors previously tested by the NFL.

Bend It Like Beckham

Still, creating the mouthguard presented challenges. Any electronics in a mouthguard have to be extremely light, small, and durable. And because a mouthguard is boiled before it’s fit to the athlete’s teeth, the components would need to withstand high temperatures.

One of the stipulations for the team’s NIH grant was that a commercial partner eventually be brought on board so that the device could eventually be brought onto the market, to reach youth and high school sports organizations. In 2015, Steve Washburn was brought on as CEO to form Prevent Biometrics, bringing with him 15 years of experience as the CEO of leading mouthguard company Shock Doctor.

The team raised around $9 million to begin the process of learning how to make the mouthguard effective, at scale, and accessible to a wider audience. It helped that one of the company’s lead investors was the $15 billion dollar company Murata Electronics, which assisted the 15-person Prevent Biometrics team in finding components for a flexible circuit board, which is held in place in the mouth with a proprietary thermoplastic polymer.

Mounted on the circuit board are four accelerometers, two on each side, and two off-center. The circuit board also includes a light and proximity sensor (to ensure that the mouthguard is securely on the player’s teeth), three LED alert lights, wireless charging componentry, and a Bluetooth module.

The accelerometers monitor the number, direction, and force of the impacts on an X-Y-Z axis, and a patented algorithm calculates the force, location, direction, and number of impacts. The data is sent by Bluetooth to an iPad app. Currently, the threshold for an impact alert is set at 50gs, but the team is currently working with researchers to determine the threshold at which an athlete should be pulled from the field.

“Our circuit board is 0.5 millimeters thick,” says Washburn. “It carries all of the wires, connects to a hundred components, and can withstand heat, pressure, moisture, and temperature… It has to have wireless charging. It has to have enough battery life to last a game. I think people take it for granted that they can pick up an iPhone every day, but [making this] is immensely complicated.”

It took three years of work to bring the mouthguard to market. As of March 2018, the beta version has been available for nine months to concussion researchers. The commercial product will be available this year to youth and high school sports organizations; with over five million young athletes playing contact sports like lacrosse, hockey, and football, that’s a lot of mouthguards. The boil-and-bite version retails for $199.

“It’s opened up the ability to measure head impact exposure in sports other than football,” says Dr. Brian Stemper, an associate professor in the joint department of biomedical engineering at Marquette University and the Medical College of Wisconsin. In August 2017, Stemper’s team started using the Prevent mouthguard to measure head impact exposure in NCAA Division III football players.

“In contact sports, traditionally, there’s this idea that it’s a single large impact that leads to the onset of concussion. We’re starting to see that at least in football, there’s a role for repetitive head impact exposure,” Stemper says. “It’s the straw that broke the camel’s back, where you have this accumulation…that eventually leads to the onset of concussions, with a head impact that’s really not remarkable.”

The military is also interested in accurately studying the role of repetitive head impacts, as Stapp so colorfully demonstrated back in the 1950s. In 2017, the Department of Defense entered in a cooperative agreement with Prevent Biometrics. “We’re tasked with gathering the first head impact data in military populations,” says Bartsch. “Basic training combatants go through hits to the head. We’re also instrumenting athletes at military academies.”

Heads in the Game

The Prevent mouthguard can’t diagnose concussions. Instead, it directs the coach to run through the CDC concussion symptoms checklist—Does the player appear dazed? Does the player have sensitivity to light? Nausea? Blurred vision?—and adds several pieces of objective data.

As part of its plan to improve player safety equipment, the NFL is evaluating different sensor-implanted mouthguards next month. The Prevent Biometrics mouthguard is one of the leading contenders. The team hopes it can prove that with more information, organizations can begin to preserve high-impact sports—from the NFL, all the way down to kids’ teams.

“We’re not trying to kill the game of football,” Stemper says. “We’re trying to make the game safer. I think that’s one realistic example—you can look at players who have higher exposure, figure out why they’re having higher exposure, and coach it out of them.”

Washburn agrees. “We strongly believe in the value of sports in kids’ development,” he says. “Some sports could be in jeopardy as a result of brain injuries. The ability to develop a product that makes sports safer and builds on what we think is an important part of society, is why so many people believe in this project.”

Correction appended, 3/1/17, 3:15 PM EDT: A previous version of this story misidentified Prevent’s funding; it is $9 million, not $6.5 million. Steve Washburn is quoted as saying that the mouthguard can withstand “heat, pressure, and temperature”; the correct quote is “heat, pressure, and moisture.” In a previous version of this article, Dr. Stemper’s title is listed as an associate professor in the joint Department of Biomechanical Engineering at Marquette University and the University of Wisconsin. His correct title is an associate professor in the joint Department of Biomedical Engineering at Marquette University and the Medical College of Wisconsin.