By Joe Lemire

Vincent Miele was an amateur boxer as a teenager, who later became a ringside physician as a medical resident while training to be a neurosurgeon at West Virginia University. Along with the renowned Dr. Julian Bailes, the two conducted a video analysis comparing a control group of typical professional boxing matches with a set of highly competitive classic bouts and a set that ended with a fatality.

Their published research showed that there were no evident differences between the latter two cohorts with regards to the quantity of punches landed and the perceived force of those punches. It was not apparent from reviewing the matches with the assistance of the Punchstat computer program that one (the competitive match) or the other (the fatal match) would result in lethal damage to the competitors.

“It’s really hard to tell,” Miele, now a neurosurgeon at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, told SportTechie. “Are they just tough? Are they getting hurt? Are the tough ones the ones who are going to get hurt? It’s hard to say when to stop a fight. I wanted to come up with something objective to stop these fights.”

The ambiguity gnawed at Miele. Around that time, he operated on a female boxer who had developed a subdural hematoma. She nearly died. He knew something had to be done.

While at West Virginia, Miele began tinkering with a mouthguard-based solution, but only after beginning his fellowship at Cleveland Clinic was the idea realized over years of painstaking work by a team that included neurosurgery chairman Ed Benzel, biomechanics engineering Ph.D. Adam Bartsch, spine clinic director Lars Gilbertson, biomedical engineer Barry Kuban and mechanical research engineer Sergey Samorezov.

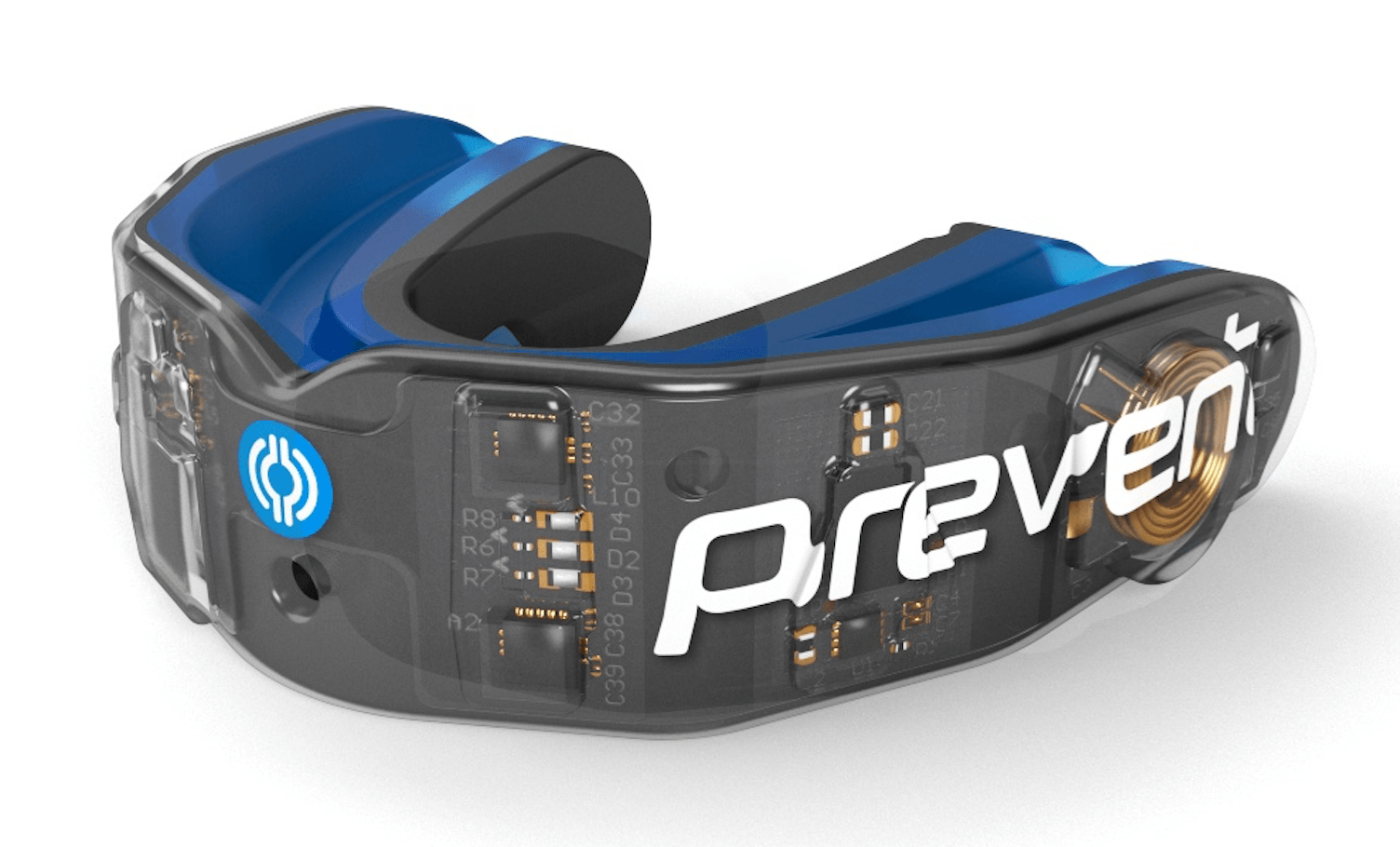

The product of their work has been spun off into Prevent Biometrics’ intelligent mouthguard that uses a flex circuit embedded with four accelerometers, each producing three channels of data, and an advanced algorithm that triangulates those 12 data points to measure head impacts in real-time. Among the metrics tabulated: linear acceleration, rotational acceleration, location on head, direction of impact and total number of impacts.

In a study published in the peer-reviewed Stapp Journal, the team reported that the mouthguard’s precision in quantifying the force of blows was within five percent. Bartsch, now Prevent Biometrics’ chief science officer, has called this accurate measurement of head impacts “the holy grail of concussion research.”

When certain thresholds are crossed, the mouthguard lights up red and the bluetooth technology alerts coaches and trainers on the sideline, so they can evaluate for a concussion or other impairment.

“If your exposure hits the red line, you’re out of the fight — it’s an electronic knockout, basically,” Miele said. “That would save some of the tougher guys that can fight through those hits. It would save their brains.”

This mouthguard, which has been tested in college and high school over a variety of contact sports, is now commercially available for the first time through a soft launch in four regions (Connecticut/Massachusetts, Minnesota/Wisconsin, Texas and Colorado) in time for the fall football season. After appearing at this year’s Consumer Electronics Show, the device was featured on “Live With Kelly and Ryan” with Kelly Ripa

Prevent Biometrics has said the NFL — which recognized the technology as a finalist in its 1st and Future startup competition last year — is testing the device this month. An NFL spokesperson said the league and union are collaborating to provide sensor-embedded mouthguards and are evaluating several commercial and research systems.

The mouthguard was originally designed for boxing, where fighters don’t wear helmets the way football players do. But in many cases helmet-based systems aren’t reliable because the headwear moves too much. As Bartsch has written, “Although a number of published head impact studies have captured impressive-looking data using helmet- or skin-mounted sensors, these approaches yield erroneous head impact measures.”

Miele said one’s back teeth are about as close to the brain stem as one can get, calling the mouthguard “the next best thing to actually screwing an accelerometer to the skull to get readings.”

“The reason a mouthguard works is because the mouthguard can securely couple to the upper arch of teeth, which is part of your skull, so it’s a way of getting a coupling to the skull by proxy,” Prevent Biometrics chief marketing officer David Sigel said. “It has nothing to do with the teeth. The only thing the teeth are doing are allowing you to connect to the head.”

Research into neurological impairment has shown that concussions themselves aren’t always the problem, and that the accumulation of sub-concussive hits are problematic. Miele likened the tallying of these hits to the old Nintendo game Mike Tyson’s Punchout in which a bar on the top of the screen tracked the totality of blows. “It’s not just the heavy punches, it’s the accumulation,” he said.

The way Little League has a strict pitch count for pitchers, Miele envisions football potentially incorporating some sort of hit count for players, especially linemen who inherently are involved in contact on every play. Syncing the mouthguard readings with video analysis can inform players and coaches of what situations and techniques lead to greater forces.

“It also can be used as a teaching tool for them,” Miele said. “How can you lower your impacts? And there’s an impetus for them to lower their impacts because they don’t want to get pulled.”

Miele is also an independent neurosurgical consultant for the NFL and the Pittsburgh Steelers. An objective head-impact measure would alleviate the pressure of making subjective decisions regarding when to remove a player with a possible concussion — but that’s not the ultimate goal.

“The NFL is nice, but again, the NFL is not the main focus of this mouthpiece, either,” he said. “If the NFL adopts something, then everybody wants to do it. But the NFL is a very small number of players — the big thing is the high school kids and even the kids younger than high school age. If we can get it to them, that’s where we’re really going to help people.”